Australia has long been referred to as a land of “drought and flooding rains”, prone to bushfires as well as intense rainfall events. Periods of hot, dry, windy weather have regularly dried out vegetation and made it susceptible to ignition, alternating with prolonged wet periods that have promoted rapid and widespread vegetation growth.

Climate change, driven by the burning of coal, oil, and gas, is worsening these extreme weather events (IPCC 2021a). The Black Summer bushfires in 2019-2020, as well as the record-breaking Great Deluge of 2022— both of which claimed lives, livelihoods, property and crops—were exacerbated by climate change (see, for example, Binskin et al. 2020; Climate Council 2022).

For the past three years, Australia has experienced wetter than average conditions, with record-breaking rainfall and floods across New South Wales (NSW), Queensland, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania (BoM 2022). This has been due to a rare ‘protracted’ La Niña event together with a negative phase of the Indian Ocean Dipole and a positive phase of the Southern Annular Mode.

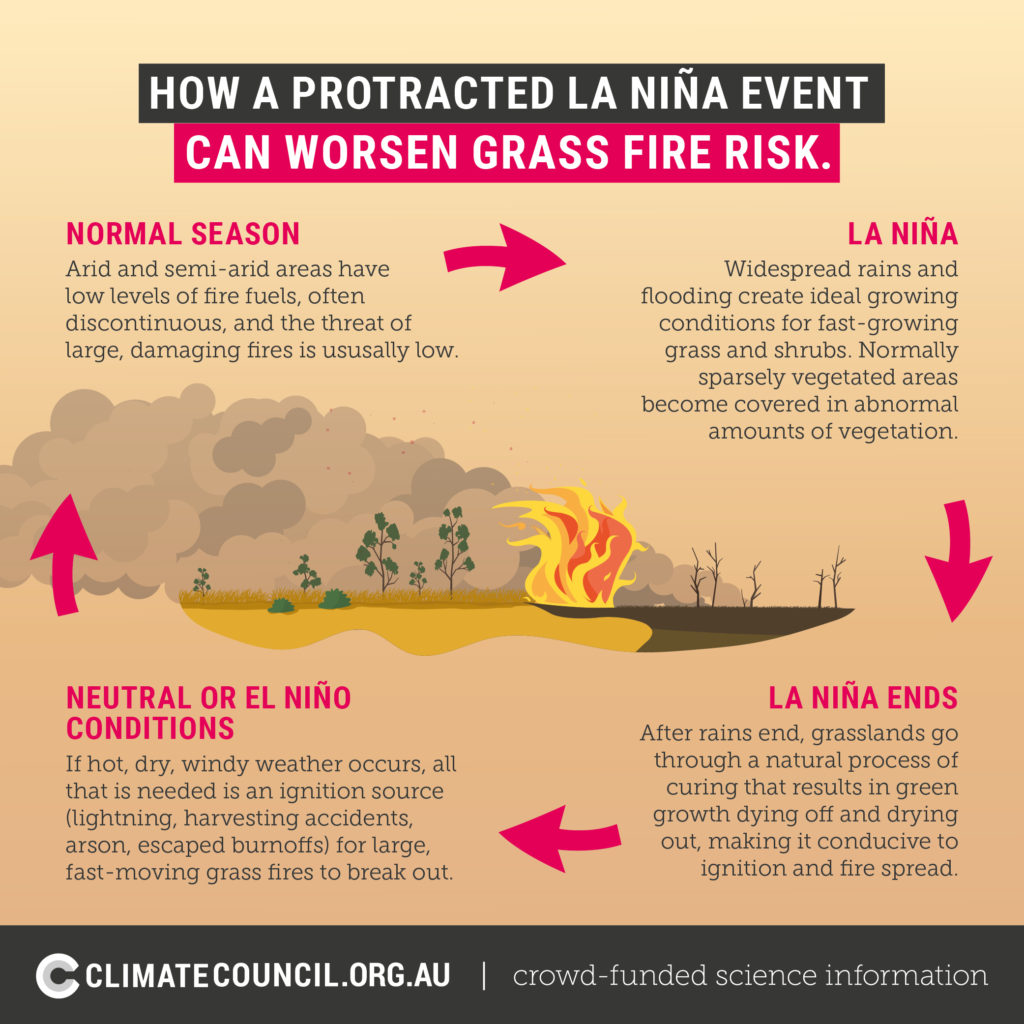

Given the years of rainfall since Black Summer, it is reasonable to expect that fire risk may have slipped from the Australian public’s consciousness. However, very wet periods often make fire services nervous, because they are a double-edged sword. On one hand, rain keeps vegetation wet, reducing the likelihood of ignition and limiting fire spread during the wet period. On the other hand, it leads to prolific growth, even in ‘desert’ areas that typically have insufficient vegetation to pose any fire risk.

The wet weather also limits the ability of land managers and fire services to carry out fire prevention and mitigation works, for example, hazard reduction burning cannot be carried out during wet conditions. When wet weather inevitably gives way to hot, dry conditions, light grasses and shrubs die and dry out and we are then left with more vegetation available to burn.

Report Key findings:

1. Australia’s three years of cooler and wetter than- average conditions, due to a protracted La Niña event, temporarily dampened our bushfire risk. However, this has led to prolific vegetation growth that’s creating powder keg conditions for future fires.

- From 2020 to 2023, Australia experienced a multiyear ‘protracted’ La Niña episode that led to recordbreaking rainfall and flooding along the east coast. These heavy rains led to prolific growth of grass and bushland, including rapid regrowth in areas scorched by the Black Summer bushfires.

- In some inland areas, fire fuel loads have a normal range of between 0.5 to 1.5 tonnes per hectare, but there are now between 4.5 and 6 tonnes per hectare following recent heavy rains. These same areas – so recently green – are now turning brown and yellow as heatwaves sweep across the country, priming grasslands to burn.

- The collective wisdom of firefighters, based on history and experience, suggests that grass fires are rarely as damaging as forest fires. However, this may not hold true during a grass fire event that occurs in conditions as extreme as the ones we now experience in a supercharged climate.

- Events in Australia, and overseas, prove that grassfires are dangerous when they occur in hot and dryconditions. If the third risk factor, of strong winds,also occurs then Australia could see grass fires unfold on a scale never-before experienced.

2. History shows that grass fires follow floods. Firefighters fear that the spring of 2023 and summer of 2023-2024 could see widespread grass fires, supercharged by climate change.

- Based on the views of fire and emergency services experts, there is an increased risk of major grass fires breaking out during periods of hot weather in Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia up to and possibly including April 2023.

- History shows that grass fires follow floods.There have been three ‘protracted’ La Niña episodes since 1950: 1954 – 1957, 1973 – 1976, and 1998 – 2001. During each of these periods there was prolific growth of vegetation, followed by extensive grass fires across Australia, then by major forest fires causing loss of life and property on the east coast, particularly in New South Wales.

- Australia experienced the most widespread grass fires ever recorded in 1974 – 1975, with about 117 million hectares burnt nationally – or about 15 percent of Australia’s land mass.

- Since then, climate change has worsened and is intensifying extreme weather. Because of this, firefighters fear that extensive grass fires that break out in hotter, drier, windier weather conditions than those experienced in 1974 – 1975 could be far more destructive and deadly, like those experienced in the United States in December 2021.

3. Australia’s protracted La Niña episode is giving way to hotter and drier conditions including the possible formation of an El Niño event. As a result, we will almost certainly see a return to normal or above normal fire conditions across most of Australia in coming months.

- Current climate models indicate that Australia could see a return to warmer and drier ‘neutral’ or even El Niño conditions towards the second half of 2023. El Niño is a naturally occurring climate cycle in the Pacific Ocean that brings hotter, drier conditions to eastern Australia, making droughts and bushfires more likely.

- Bushfire danger across Australia is rising due to climate change. Significant bushfires in Tasmania and New South Wales in 2013, and the Black Summer bushfires in 2019 – 2020, showed that El Niño is no longer needed to produce a bad fire season – even a “neutral” phase of El Niño- Southern Oscillation (ENSO) can now produce periods of Extreme and Catastrophic fire danger.

- If an El Niño event does develop during 2023, this will further exacerbate the threat of both grassfires and major forest fires.

4. Governments must prepare for a potentially devastating fire season ahead, while stepping up efforts to move beyond fossil fuels and ensure greenhouse gas emissions plummet this decade.

- Governments at all levels should prepare for a dangerous fire season later in 2023, and help communities cope with worsening and compounding climate impacts while working to prevent or manage disasters more effectively.

- Emergency services and land management agencies need more funding to prevent, prepare for and to respond to escalating disasters, as well as needing more full-time staff and volunteers.

- Emergency management agencies, state and local governments also need permanent arrangements rather than ad hoc solutions to initiate and manage long-term disaster recovery efforts due to worsening climate change fuelled disasters.

- Communities need more funding for education and resilience projects.

- Efforts to adapt and build resilience to climate impacts must go hand-in-hand with much stronger efforts to move beyond fossil fuels and rapidly cut emissions if we are to avert even worse catastrophes.