You might have heard that Brisbane is set to host the Olympic Games in 2032. And while this is a big win for Brisbane it could also be a big win for the planet, since the 2032 Games will be the first climate positive summer Olympics.

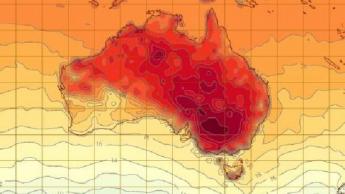

Sporting events in Australia, and across the planet, are under threat from climate change. Summer sports, already hazardous with high temperatures and potentially noxious conditions such as the smoke haze created by the Black Summer fires, stand to suffer further with heatwaves in Melbourne and Sydney likely to reach 50˚C by the year 2040, making outdoor sport untenable.

The sporting industry isn’t just a witness of climate change but a contributor, too, with estimates placing sports’ global emissions on par with those of Spain. And while sport is a contributor to greenhouse gas emissions, its star power and command of global attention also make it a promising advocate for solutions.

The promise of a climate positive Olympics—and all those following 2030—is a step in the right direction, but only if it’s followed up with successive steps to make tangible and realised change. So what does being climate positive mean? How does it happen? And who’s responsible?

What is a climate positive Olympics?

A ‘climate positive’ Olympics describes an Olympics that doesn’t settle for reducing its emissions to zero and offsetting those emissions it can’t avoid (carbon neutral), but goes further to absorb or remove more than it produces to become ‘carbon negative’—a synonym for climate positive.

“This way, the Olympic Games will become climate positive, meaning that the carbon savings they create will exceed the potential negative impacts of their operations,” the International Olympic Committee says.

It’s not difficult to imagine the emissions toll from a traditional Olympic games: the international travel of countless far-flung athletes, the transport of masses of specialised equipment, and the construction of brand-new infrastructure (transport systems, Olympic villages, stadia, and Olympic parks) whose carbon footprint can be gauged by recalling that cement, for instance, is the source of about 8% of the world’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. So, how does one host a climate positive Olympics?

How to host a climate positive Olympics

While the details of a climate positive Brisbane 2032 Olympics are yet to be laid out, the International Olympic Committee and other interim host nations—Japan (2021), France (2024), the United States (2028)—provide an outline for how emissions might be reduced.

Infrastructure

One simple change will see Brisbane 2032 using pre-existing buildings to house athletes and host sports wherever possible:

- Athletes and team officials will be accommodated in pre-existing hotels across South East Queensland, including the Gold Coast

- Athletics and basketball competitions are planned to take place in the Albion Precinct

- Archery will be in the South Bank Cultural Forecourt

- Equestrian and BMX will be at Victoria Park

- Table tennis and fencing will take place in the Exhibition Centre

- Even the Gabba has been earmarked as a potential host for the opening and closing ceremonies.

Pre-existing venues around Brisbane will be co opted to support sports, such as archery—aimed to be held in South Bank’s Cultural Forecourt.

Sporting complexes could also implement solar systems and batteries to operate on 100% renewable electricity. One such renewable facility is Queensland’s Metricon Stadium, host to the 2018 Commonwealth Games, that possesses a ‘solar rim’—a five metre-wide ring of solar panels around the entire inner roofline—that supplies roughly 20 percent of the stadium’s total electricity needs.

Though a bespoke ‘Olympic village’, and potential stadium, is planned, Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk has stated that, where possible, the venues used by the games will be pre-existing.

Transport and travel

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) has identified transport as one of sport’s largest sources of emissions. In order to curb these emissions, the IOC recommends:

- Meet virtually, wherever possible

- Use public, not personal, transport

- Share vehicles to reduce total number of journeys

- Use fuel-efficient and low/zero-emissions vehicles

While many of these solutions are aimed at the emissions associated with sportspeople, those derived from fans and spectators—driving to a large-scale sporting event, for instance—can be reduced by encouraging the use of public transport, cycling, or walking such as the ‘Fan Trail’ used in the 2011 Rugby World Cup in Auckland that featured entertainment and food and drink en route.

Infrastructure and transport aren’t the only way to counter a games’ carbon footprint. Brisbane 2032 might also co opt some of the emissions reduction practices of the upcoming Tokyo, Beijing (Winter Olympics), and Paris games, such as those outlined below.

Influence from the International Olympic Committee and upcoming Olympic Games

If thrift is the spirit of Brisbane 2032, we might give recognition to the International Olympic Committee (IOC) who, in 2014, adopted sustainability as a primary pillar. In recent years the IOC has, with increasing breadth and boldness, made moves to reduce its carbon footprint and address ‘the growing climate crisis’, promising to collaborate with each Olympic Host City to achieve a climate positive games.

“Climate change is a challenge of unprecedented proportions, and it requires an unprecedented response,” said IOC President Thomas Bach. “Looking ahead, we want to do more than reducing and compensating our own impact. We want to ensure that, in sport, we are at the forefront of the global efforts to address climate change and leave a tangible, positive legacy for the planet.”

The IOC headquarters in Switzerland leads by example on sustainability, hosting a fleet of renewable hydrogen-fuelled vehicles and a renewable hydrogen production and refuelling station.

A zero-emission hydrogen fuel cell Toyota Mirai delivered to the International Olympic Committee. Photo: Philippe Woods/IOC

Upcoming Olympics promise to reduce their emissions to zero too:

- Tokyo 2021 is aiming for carbon neutrality

- Olympic Partner Toyota will provide zero-emissions vehicles, including cars powered by renewable hydrogen, for the Tokyo Olympic fleet

- For Beijing 2022, all venues will be powered by renewable energy

- Paris 2024 is on track to becoming carbon-neutral

- For LA 2028, all venues already exist

The commitments of the IOC and its Host Cities are valiant and, for the attention they garner for climate action, invaluable. That makes the Brisbane Olympics 2032 so important. The world’s attention will be turned to the land down under, to Queensland—where the sun does shine—when Brisbane will need to set the bar to new heights and show the world how a climate positive summer games is done.

To learn how Australian sport can already cut back on carbon emissions, read our sports report, Game, Set, Match: Calling Time on Climate Inaction.