This article was originally published by The Conversation.

Written by Wesley Morgan, Climate Council researcher, Griffith University

The first week of the United Nations climate talks in Glasgow are drawing to a close. While there’s still a way to go, progress so far gives some hope the Paris climate agreement struck six years ago is working.

Major powers brought significant commitments to cut emissions this decade and pledged to shift toward net-zero emissions. New coalitions were also announced for decarbonising sectors of the global economy. These include phasing out coal-fired power, pledges to cut global methane emissions, ending deforestation and plans for net-zero emissions shipping.

The two-week summit, known as COP26, is a critical test of global cooperation to tackle the climate crisis. Under the Paris Agreement, countries are required, every five years, to produce more ambitious national plans to reduce emissions. Delayed one year by the COVID pandemic, this year is when new plans are due.

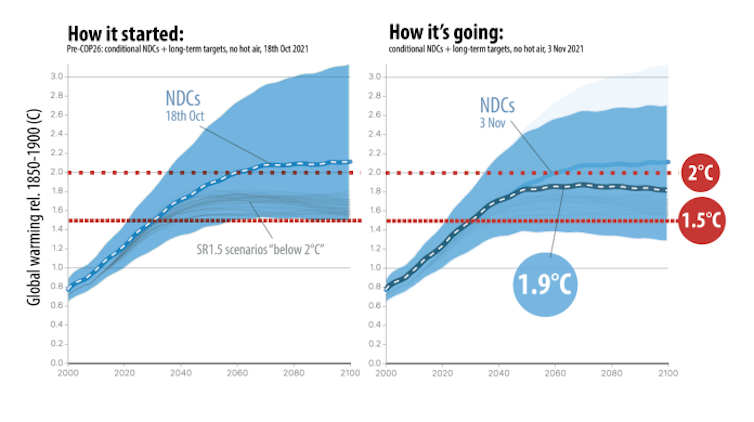

Pledges made at the summit so far could start to bend the global emissions curve downwards. Credible projections from an expert team, including Professor Malte Meinshausen at the University of Melbourne, suggest if new pledges are fully funded and met, global warming could be limited to to 1.9℃ this century. The International Energy Agency came to a similar conclusion.

This is real progress. But the Earth system reacts to what we put in the atmosphere, not promises made at summits. So pledges need to be backed by finance, and the necessary policies and actions across energy and land use.

A significant ambition gap on emissions reduction also remains, and more climate action is needed this decade to avoid catastrophic warming. Achieving necessary emissions reductions by 2030 will be a key focus of the second week of the Glasgow talks, especially as global emissions are projected to rebound strongly in 2021 (after the drop induced last year by COVID-19).

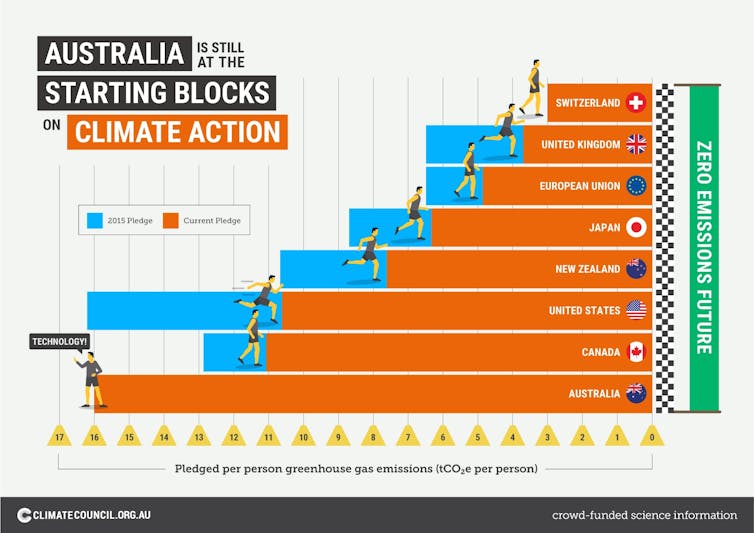

For its part, Australia contributed virtually nothing to global efforts in Glasgow. Alone among advanced economies, Australia set no new target to cut emissions this decade. If anything, this week added to Australia’s reputation as a member of a small and isolated group of countries – with the likes of Saudi Arabia and Russia – resisting climate action.

Global momentum: What did major powers bring to Glasgow?

Since the last UN climate summit we’ve seen a worldwide surge in momentum toward climate action. More than 100 countries – accounting for more than two-thirds of the global economy – have set firm dates for achieving net-zero emissions.

Perhaps more importantly, in the lead up to the Glasgow summit the world’s advanced economies – including the United States, the United Kingdom, the European Union, Japan, Canada, South Korea and New Zealand – all strengthened their 2030 targets. The G7 group of countries pledged to halve their collective emissions by 2030.

Major economies in the developing world also brought new commitments to COP26. China pledged to achieve net-zero emissions by 2060 and strengthened its 2030 targets. It now plans to peak emissions by the end of the decade.

This week India also pledged to achieve net-zero by 2070 and ramp up installation of renewable energy. By 2030, half of India’s electricity will come from renewable sources.

The opening days of COP26 also saw a suite of new announcements for decarbonising sectors of the global economy. The UK declared the end of coal was in sight, as it launched a new global coalition to phase out coal-fired power.

More than 100 countries signed on to a new pledge to cut methane emissions by 30% by 2030. More than 120 countries also promised to end deforestation by 2030.

The US also joined a coalition of countries that plans to achieve net-zero emissions in global shipping.

But this week the developed world fell short of fulfilling a decade-old promise – to deliver US$100 billion each year to help poorer nations deal with climate impacts.

Fulfilling commitments on climate finance will be critically important for building trust in the talks. For its part, Australia pledged an additional A$500 million in climate finance to countries in Southeast Asia and the Pacific – a figure well short of Australia’s fair share of global efforts. Australia also refused to rejoin the Green Climate Fund.

Missing the moment: The Australian Way

While the rest of the world is getting on with the race to a net-zero emissions economy, Australia is barely out of the starting blocks. Australia brought to Glasgow the same 2030 emissions target that it took to Paris six years ago – even as key allies pledged much stronger targets.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison arrived with scant plans to accompany his last-minute announcement on net-zero by 2050. The strategy titled The Australian Way, which comprised little more than a brochure, failed to provide a credible pathway to that target. It was met with derision across the world.

On the way to Glasgow, at the G20 leaders meeting in Rome, Australia blocked global momentum to reduce emissions by resisting calls for a phase out of coal power. Australia also refused to sign on to the global pledge on methane.

Worse still, Australia is using COP26 to actively promote fossil fuels. Federal Energy Minister Angus Taylor says the summit is a chance to promote investment in Australian gas projects, and Australian fossil fuel company Santos was prominently branded at the venue’s Australia Pavilion.

The federal government is promoting carbon capture and storage as a climate solution, despite it being widely regarded as a licence to prolong the use of fossil fuels. The technology is also eye-wateringly expensive and not yet proven at scale.

The closing stretch

Week one in Glasgow has delivered more climate action than the world promised in Paris six years ago. However, the summit outcomes still fall well short of what is required to limit warming to 1.5℃. Attention will now turn to negotiating an outcome to further increase climate ambition this decade.

Vulnerable countries have proposed countries yet to deliver enhanced 2030 targets be required to come back in 2022, well before COP27, with stronger targets to cut emissions.

This week, the United States rejoined the High Ambition Coalition, a group of countries from across traditional negotiating blocs in the UN climate talks. Led by the Marshall Islands, the group was crucial in securing the 2015 Paris Agreement.

In Glasgow, this coalition is pressing for an outcome that will keep the world on track to limiting warming to 1.5℃.

But significant differences persist between the US and China. Many developing countries want to see more commitment to climate finance from wealthy nations before they will pledge new targets. Can consensus be reached in Glasgow? We’ll be watching the negotiations closely next week to find out.

Wesley Morgan, Research Fellow, Griffith Asia Institute and Climate Council researcher, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.