Blackened forests and charred properties left behind by devastating bushfires are well known to Australians, but flooding is the most expensive extreme weather disaster in this country. Floods pose the greatest climate risk to Australian homes, a fact that’s reflected in our Climate Risk Map, where 80% of the properties classified as high risk by 2030 are most at risk of riverine flooding. So let’s unpack what this means for Australians in these areas.

What are the main types of floods?

The three major types of flooding risk identified on the Climate Risk Map are riverine flooding, surface water flooding and coastal inundation. Surface water flooding (also called pluvial flooding) is when the ground is oversaturated and drainage systems overflow, causing excess water to build up. Coastal inundation is when seawater temporarily or permanently floods an area due to a combination of sea-level rise, high tides, wind and/or waves. Riverine flooding is when a river exceeds its capacity, inundating nearby areas. In the near term, the primary risk to homeowners is riverine flooding, so let’s explore this more.

Which electorates are most at risk of riverine flooding?

The Climate Risk Map allows you to easily identify the most at-risk electorates for riverine flooding based on the percentage of medium-to-high risk properties. According to our Uninsurable Nation Report (which focuses on the percentage of high-risk properties only), the top five are Nicholls in Victoria, Richmond in New South Wales, and in Queensland – Maranoa, Brisbane and Moncreiff. Many of these electorates were affected by the devastating floods of early 2022.

In Nicholls, almost 25,000 properties will be at ‘high risk’ by 2030. Homes are deemed as being at high risk when the projected annual damage cost is equivalent to 1% or more of the property replacement cost. These properties are classified in our analysis as ‘uninsurable’ because, at this level of risk, insurance premiums become effectively unaffordable. An extraordinary 80 to 90% of homes around the township of Shepparton (e.g. Shepparton, Shepparton North, Kialla, and Kialla West) will be effectively uninsurable by 2030 because of their risk of flood damage (and most of these homes would already be experiencing this level of flood risk).

What does this mean for homeowners?

Floodwaters creep under doorways, leave behind mud and can cause structural damage. Water-damaged homes and household items are also susceptible to mould and mildew growth. Insurance companies generally evaluate the flood risk to homes based on flood maps (such as the National Flood Information Database) and other information on building type, previous claims and location.

When they determine there is a high risk of flood damage, the price to insure homes against this individual risk can skyrocket. It is common for people in high-risk areas to opt-out of flood insurance for their homes because of cost. Unfortunately, this often results in the most at-risk homes having the least insurance coverage.

Often, homeowners who can least afford it are feeling climate impacts the most. In the Richmond electorate – which encompasses coastal towns such as Hastings Point, Pimlico, and Mullumbimby — riverine flooding from the Richmond River and its tributaries, in combination with high tides, results in increased risk. We saw the effects of this in March 2022, when a 1.8 metre king tide combined with record-breaking floods inundated roughly 6,000 homes in the Ballina area. The latest Census data shows median weekly household incomes in this area are well below the national average, with more part-time workers and fewer full-time workers compared to the national average.

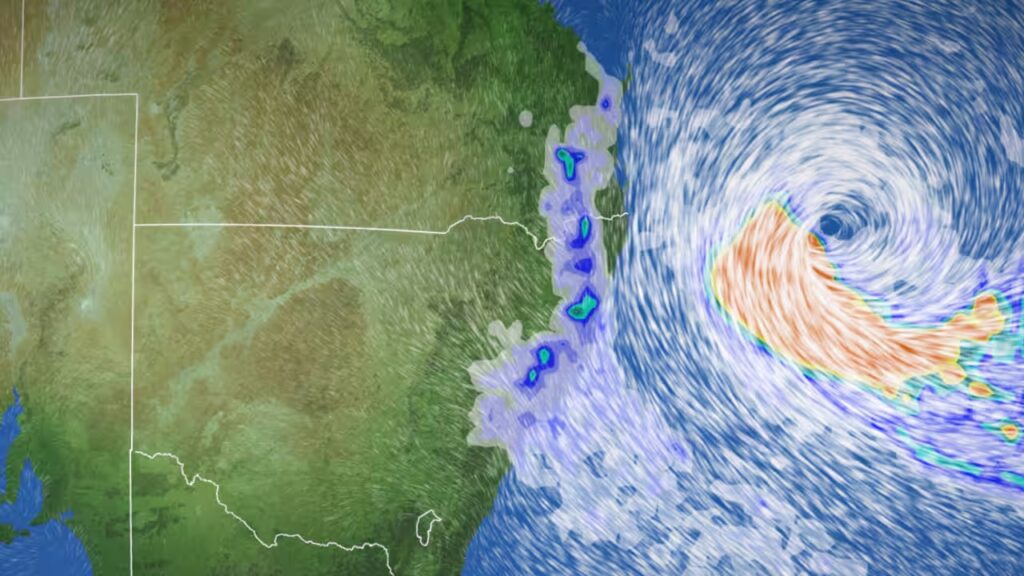

So where is this risk coming from?

The risk of properties to climate change and extreme weather comes from a number of factors. These include the type of building and how well it is built (ie. how old the building is and the standard to which it was built) and also the building’s exposure to different extreme weather events (this is influenced by factors such as location, and proximity to rivers or forests, elevation above sea level etc.). Climate change is adding to the risks already faced by properties – and those living there – by supercharging extreme weather. In the case of flood risk, a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture (around 7% on average for every degree of global warming) and has more energy with which to fuel storms. This means that with climate change we can expect more of our rain to fall in the form of short-duration, intense downpours, which raises the risk of flooding. Across Australia, there has already been an observed increase in the proportion of rain coming from short-duration heavy rainfall events.

If we’re to learn a lesson from the catastrophic flooding that we are now seeing happen in Australia every few years, it’s that we are severely underprepared. We urgently need to address the root cause of the heightened storm threat – climate change.

Elly Bird, Councillor, Lismore City Council

What can we do?

The number one thing Australia needs to do is get national emissions plummeting – NOW. Greenhouse gasses being pumped into our atmosphere at record levels are warming our planet and fuelling extreme weather events, like the 2022 floods.

You can use our new Climate Risk Map to understand how your region could be affected by riverine flooding and other extreme weather disasters fuelled by climate change. Adjust the hazard filter to show riverine flooding and zoom into your electorate, local government area or suburb to see how houses in your area might be affected.

Then, send the map to your federal candidate to remind them to #PutClimateFirst.

Now is the time for Government to lead the country in delivering on an ambitious emissions reduction target this decade to protect communities like ours from the future climate shocks that we know are coming and that we are living every single day.

Elly Bird, Councillor, Lismore City Council