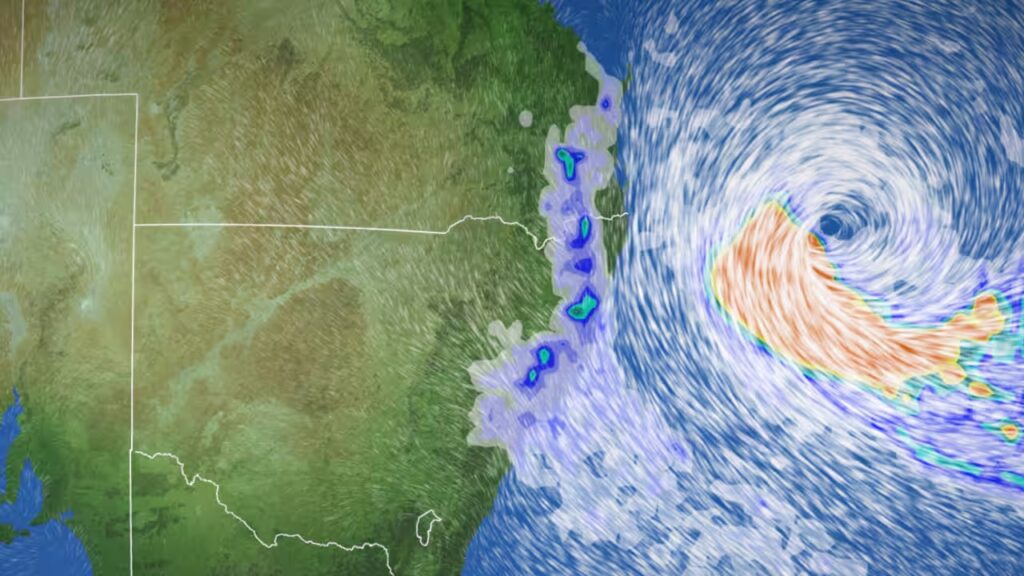

Four million Australians living in Australia’s third largest city and the heavily populated regions nearby were warned to get ready for Tropical Cyclone Alfred. Understandably, the anxiety surrounding its landfall was high.

This storm hit a lot further south than Australia’s east coast communities and emergency services are used to, moving slowly and erratically as it tracked towards Brisbane; drawing up energy from a hot and moist atmosphere and ocean as it crept closer.

In the end, the Category 2 tropical cyclone was rapidly downgraded upon making landfall. But its slow movement transformed Tropical Cyclone Alfred into a prolonged and dangerous event that caused torrential rains, coastal flooding, and powerful winds across large swathes of the country, with communities impacted as far north as Hervey Bay and as far south as Coffs Harbour over 600km away.

The intensity and devastation of this event was fuelled by climate pollution in three ways:

1. Record hot ocean temperatures in the Coral Sea over summer 2024-25 helped fuel its intensity.

2. Storm surges and wind-driven waves from Tropical Cyclone Alfred rode on higher seas, made worse by climate change.

3. A hotter, wetter atmosphere made the extreme rainfall worse than it otherwise would have been.

report key findings

1. Tropical Cyclone Alfred was more intense and damaging due to climate pollution, as storm surges rode in on higher seas and washed away iconic beaches along 500 kilometres of coastline. Wild winds and extreme rainfall prompted the highest number of emergency call outs recorded in Queensland’s history.

- Tropical Cyclone Alfred formed in the Coral Sea, where sea surface temperatures in summer 2024- 25 were the highest on record. Excess ocean heat, driven by climate pollution from coal, oil and gas, provided more fuel for the wild winds, record waves and intense rainfall that followed.

- Storm surges and wind-driven waves from Tropical Cyclone Alfred rode on higher seas due to climate pollution. This led to a series of damaging waves, as tall as a four-storey building. A 12.3 metre wave was the highest ever recorded on the Gold Coast. This caused beach erosion so extreme that beaches disappeared, with sudden drops up to 6 metres high across newly formed dunes along Surfers Paradise.

- Wind gusts of over 120kmh (recorded in Byron Bay) in NSW and 107kmh (Gold Coast) in Queensland ripped trees out of the ground, peeled roofs off houses and damaged property up and down the coast.

- The electricity network was severely disrupted, as power lines were damaged, and half a million properties across New South Wales and Queensland were plunged into darkness. Queensland experienced a record high number of power outages caused by an extreme weather event.

- Significant rainfall was dumped on a number of communities. Brisbane experienced its wettest day in 50 years (since Tropical Cyclone Wanda) with 275mm recorded overnight to March 10. Hervey Bay experienced its heaviest daily downpour in 70 years, with more than 100mm in a single hour, while Nambour experienced its heaviest March rainfall in over a century.

2. Many of the places hit by Tropical Cyclone Alfred are the same places still rebuilding and recovering from recent major flooding events. These communities are being pushed to their limit by repeated damaging extreme rainfall events.

- A dozen local government areas (LGAs) in Queensland were under disaster declarations as Cyclone Alfred approached. All of those areas experienced flooding in 2022.

- Fourteen local government areas in New South Wales were under disaster declarations as Alfred approached, and some of them (Clarence Valley, Mid-Coast and Port Macquarie-Hastings) are among the most disaster-impacted LGAs in the state, having experienced fires, storms and floods multiple times since 2019.

- Brisbane has faced four major floods in the past 15 years (2011, 2013, 2022 and 2025). As climate change drives more frequent disasters, it is exhausting, traumatic and costly for communities affected over and over again.

- Studies have shown that, in the aftermath of severe storms, survivors demonstrated a 25% increase in the onset of depression, and that the more you’re exposed to floodwaters in your home or business the worse the mental health impacts will be.

3. Tropical Cyclone Alfred was a slow-moving storm that gave communities and emergency responders time to prepare. But its prolonged nature meant that the impacts lasted longer, resulting in widespread damage which must be added to the high costs we’re all paying due to worsening extreme weather.

- In the months ahead, affected people and communities will face the mounting costs of recovery and rebuilding. An “insurance catastrophe” has been declared, with more than 63,000 claims already made. It is estimated the damage bill could run into billions of dollars and pose a threat to inflation.

- The average cost of extreme weather sits at $1,532 per household nationwide (based on 2022 figures), with higher taxes, rising insurance, more uninsured damage and higher prices paid due to supply chain disruptions all factored in. This figure is expected to rise to more than $2,500 per household by 2050.

- Collectively, the storms and floods that affected Southeast Queensland and coastal New South Wales in February and March 2022 were equal to Australia’s costliest ever extreme weather event, at $5.56 billion in insured losses arising from more than 236,000 claims.

- The cost of extreme weather disasters in Australia has more than doubled since the 1970s and the higher frequency of disasters is pushing up insurance premiums for us all. Australians are collectively paying an inflation-adjusted $30 billion more today on insurance than they were only 10 years ago.

- While Australian families, businesses, and communities bear these costs, many fossil fuel corporations that sell the polluting products overheating our planet continue to rake in eye-watering profits. Globally, the oil and gas industry takes between $US3 trillion and $US4 trillion a year in revenue.

4. Our weather is now more chaotic, unpredictable and dangerous due to climate pollution, which presents challenges for us all.

- After the immediate dangers of a flood subsides, the recovery affects people’s health and wellbeing. From water contamination, to mould, to increases in mosquito borne disease and, of course, the trauma of experiencing the disaster and aftermath.

- The latest research shows for every degree of global warming, Australians will experience 7-28% more rain for hourly events, and 2-15% more for longer duration events; a range significantly higher than the 5% typically accounted for in Australia’s flood planning standards.

- Over the course of Cyclone Alfred, 2.3 million days of learning were lost across 1,804 schools closed in Queensland and New South Wales. A recent Climate Risk Index report found two thirds of our schools already face high climate risk, and this is expected to rise to 84% by 2060.

- While Australia is now cutting climate pollution, it is not fast or far enough to do our fair share in limiting global heating to well under 2 degrees. We must slash climate pollution fast to reduce costly storm damages, as well as prepare communities and our infrastructure for the disasters we cannot avoid.

5. The southward drift of storms like Tropical Cyclone Alfred is a preview of what to expect if we keep extracting and burning fossil fuels, like coal, oil and gas. The future safety and prosperity of Australians depends on how rapidly we cut climate pollution this decade.

- Cyclones are fuelled by ocean heat and moisture. As the oceans heat up scientists worry that the cyclones we do have may track further south towards heavily populated areas and reach their maximum intensity closer to the coast.

- Heavy rainfall events that cause severe flooding are likely to intensify and become more common. Each degree of further warming could double the frequency of intense rainfall events around the world.

- Sea levels are continuing to rise, which will contribute to more damaging swells, coastal flooding and erosion.

- Australians are already paying dearly for the failure of former governments, here and around the world, to slash climate pollution. The severity of events we face into the future rests entirely on how quickly and deeply the world cuts pollution from coal, oil and gas.

- Any move to prolong the use of fossil fuels, either through approvals of new coal and gas projects or policies that delay the switch to renewable power backed by storage, will make future disasters more harmful on our society and endanger our children’s lives even further for decades to come.