Our future depends on urgent and decisive action to respond to the climate crisis in the 2020s, as scientific consensus makes clear our window to avoid catastrophe is closing.

In November 2021, governments from around the world convened at the UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow (COP26) to respond to the rapidly escalating climate challenge. The pledges made at Glasgow have profound implications for the next Australian Government, particularly the need to promptly strengthen its 2030 emissions reduction target (UNFCCC 2021). A significantly stronger 2030 target will restore Australia’s international standing, and unlock economic opportunities for Australians in clean industries and exports. Most importantly, it will better align with the global goal to limit warming to 1.5°C, which would help protect Australians, our Pacific neighbours and the global community from catastrophic climate change.

The Australian Government arrived in Glasgow as an outlier among its international peers; one of just a handful of countries that failed to strengthen its 2030 target. It then failed to join a number of landmark pledges, including the Global Methane Pledge and a new UK-led commitment to phase out coalfired power. Instead, it used its presence in Glasgow to promote the continued burning of fossil fuels. It quickly became clear that the Australian Government had fallen even further out of step with the rest of the world. As a result, Australia’s international reputation took a further battering.

Multiple lines of evidence strongly suggest that we can no longer limit warming to 1.5°C without a temporary overshoot. The global average temperature rise will likely exceed 1.5°C during the 2030s (IPCC 2021). There’s little time left to limit global warming below catastrophic temperature rises. Breaching 1.5°C of warming significantly increases the risk of triggering abrupt, dangerous and irreversible changes to the climate system. Every fraction of a degree of avoided warming matters, and will be measured in lives, species and ecosystems saved. We must do everything possible to deeply and rapidly cut our emissions, while also preparing for climate impacts that can no longer be avoided.

This briefing unpacks the key takeaways for Australia from the COP26 climate conference in Glasgow, in particular the urgent need for Australia to catch up with the rest of the world. The only way to do this is with a strong 2030 target and a suite of credible climate policies that accelerates the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy and electrification.

“Policy decisions made today are so important because our future depends on how quickly and decisively we respond to the climate challenge in the 2020s. So much is at stake: our whole way of life, our health, our livelihoods. Our window to avoid catastrophe is closing …We know that we must do everything possible to limit warming to 1.5C, and that this requires emissions to plummet this decade. We know that every fraction of a degree of avoided warming matters, and will be measured in lives, species and ecosystems saved.

Climate Council CEO Amanda McKenzie

Key Findings

1. The Morrison government’s weak 2030 target is out of step with the rest of Australia and the world; effectively setting us on a path towards catastrophic global warming.

- The Australian government’s 2030 target (which is 26-28% below 2005 levels) is pitiful. Australia’s current policies are consistent with catastrophic global warming of more than 3°C. › In effect, the Australian government is planning to do half of what the Business Council of Australia is calling for, and around half of what of our strategic allies have committed to.

- The Australian Labor Party has pledged, if elected, to cut emissions by 43% by 2030 (based on 2005 levels). This will lower power bills and emissions, while creating more jobs and economic opportunities. However, it is not enough to avert dangerous levels of global warming.

- Most Australian states and territories are on the way to achieving higher 2030 emission reduction targets. On the whole, that adds up to a de facto nation-wide 2030 target of 37-42% below 2005 levels.

- The Climate Council is calling for Australia to reduce its emissions by 75% below 2005 levels by 2030. As a first step, the federal government should match key allies and commit to halving emissions this decade.

2. Australia signed up to the Glasgow Climate Pact, which collectively commits the world to a 45% reduction in emissions this decade (relative to 2010 levels) and requires all countries to increase their 2030 emissions reduction targets.

- Governments agreed to revisit and strengthen their 2030 targets ahead of the 27th Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP27) in November 2022, and align them with climate action required to limit warming to 1.5°C.

- The Glasgow Climate Pact specifically urges those countries that failed to come to COP26 with a new 2030 emissions target – including Australia – to set a stronger 2030 target as soon as possible.

- The Australian Government is the only major developed country to fail to update its 2030 target since 2015.

- Federal ALP plans to increase our national 2030 target to 43% would mean bringing Australia closer to a path of credible climate action. However, it effectively means other countries need to do more than Australia is in order to avert dangerous levels of global warming.

3. The world has effectively called time on coal. Increasingly, countries are accelerating their shift away from fossil fuels, which will dry up demand for Australian fossil fuel exports.

- The Glasgow Climate Pact explicitly agrees to curtail coal-fired power – the first time a global agreement on this has been reached in 30 years of climate talks.

- There has been a 76% reduction in proposed coal-fired power stations since the 2015 Paris Agreement. All significant international public finance for coal has ceased, and the private sector is also moving away from financing coal.

- “International finance is being redirected to help countries reliant on coal switch to clean energy alternatives faster. The Asian Development Bank has launched a multi-billion-dollar fund to buy up coal power stations in our region and retire them early.

- Key markets for Australian fossil fuel exports (including China, Japan, India and South Korea) as well as countries thought previously to be growth markets (such as Vietnam and the Philippines) are setting net-zero targets and transitioning away from coal and gas.

4. Accelerating climate action at home will protect lives and livelihoods, and unlock Australia’s world-leading potential for clean industries and exports.

- Under a global average temperature rise of 1.1°C, Australia is already experiencing more powerful storms, destructive marine and land heatwaves, and a new age of megafires. This is harming Australian lives, and livelihoods.

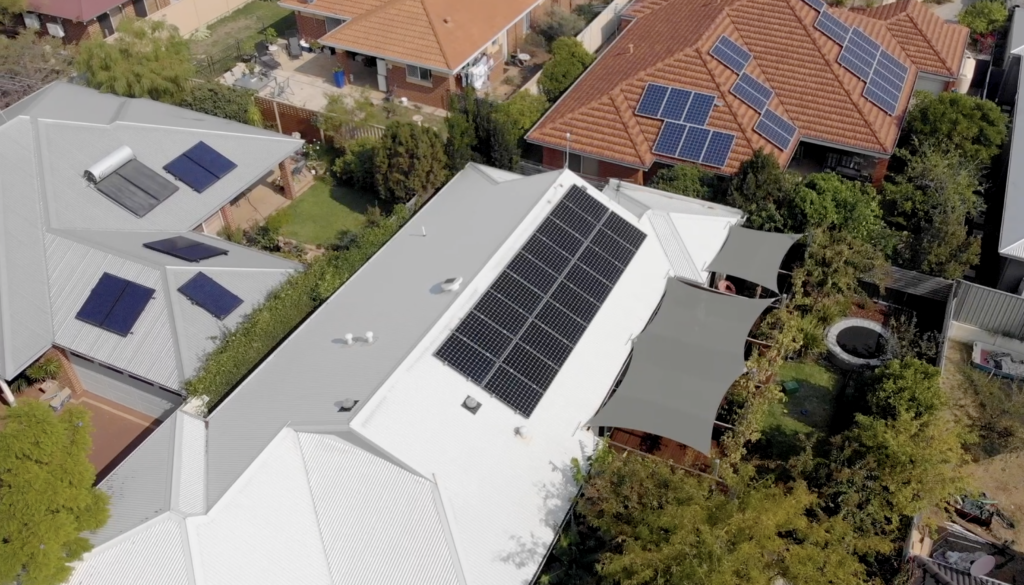

- Australia has the most sunlight per square metre of any continent in the world, and offshore wind resources that rival those of the North Sea. Cutting energy waste and shifting to renewable electricity this decade would save Australians $20 billion per year on average in fuel and power bills.

- With the right policies, Australia could establish a clean exports mix that meets the needs of growing economies in Asia worth hundreds of billions per year – far exceeding the value of today’s fossil fuel exports.

- Any expansion of gas or coal in Australia runs counter to the global race towards net zero emissions. It exposes households and businesses to higher costs, stranded assets and carbon tariffs.