Australia’s Bureau of Meteorology declared the latest El Niño has ended. This El Niño was amplified by climate change, which pushed global temperatures to new heights.

The burning of coal, oil, and gas is supercharging Australia’s climate and simultaneously disturbing other climate phenomena, like sustained periods of warming (El Niño) or cooling (La Niña) in the central and eastern Pacific, which are part of a natural cycle.

Because sea surface temperatures in the central Pacific Ocean have “cooled substantially”, the Bureau of Meteorology announced that the recent El Niño ended on 21 April, 2024.

What is El Niño again?

El Niño occurs when the sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific are significantly warmer than average, leading to a shift in rainfall – away from the western Pacific Ocean and eastern Australia, and toward the central and eastern Pacific Ocean.

Indian Ocean Dipole Event

A positive Indian Ocean Dipole event occurred alongside the most recent El Niño. The Indian Ocean Dipole is another key driver of our weather. We can think of it as the El Niño/La Niña of the Indian Ocean. When we have both an El Niño event and a positive Indian Ocean Dipole, the drying effect can be more widespread across the continent and more pronounced.

The relationship between El Niño and climate change

The connection between El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events and climate change is complicated. However, the CSIRO has shown that both El Niño and La Niña events have become more frequent and intense due to climate change.

What happened during our El Niño Summer?

This El Niño was declared in September 2023, when Australians were preparing for some hot and dry months ahead, and the return of dangerous bushfire conditions. Since then, 2023 has been confirmed as the hottest year on record and our Great Aussie Summer was marred by climate whiplash, hurtling our communities between extreme heat and fatal floods.

The start of the fire season was ferocious, and it came too soon. Climate change closed the window we once used to conduct critical hazard reduction burns; suddenly swinging from too wet, to too dry and dangerous. Catastrophic fire warnings were recorded around the country, and homes and lives were lost to deadly blazes all before December. Off the back of the driest three months ever recorded came a deluge of floods and storms, once again pushing emergency services to capacity.

This El Niño Summer was originally expected to exacerbate dry and hot conditions across the country, increasing the likelihood of drought and bushfires. Instead, it battered communities with almost every possible extreme, catching emergency services off guard, straining capacity, and challenging conventional meteorological wisdom.

Almost every state and territory has broken an extreme weather record. Towns in the Pilbara, Western Australia and outback Queensland recorded new January temperature records just shy of 50°C. Parts of South Australia, Tasmania and Victoria all recorded record rainfalls in December or January, as overall temperatures remained high, while the unusually slow and early arrival of Cyclone Jasper in Queensland dumped enormous amounts of rainfall consistent with what’s expected of cyclones on an overheating planet.

“It hasn’t been the summer that many were expecting. But it has shown many, many markers of a planet made warmer through the burning of fossil fuels.”

Dr Simon Bradshaw, Climate Council Research Director

What does this mean for our weather?

In a rapidly changing climate, history may no longer be our best guide for what’s next. By changing the climate, we are changing the conditions that govern natural climate drivers, like El Niño, and the conditions under which all weather forms.

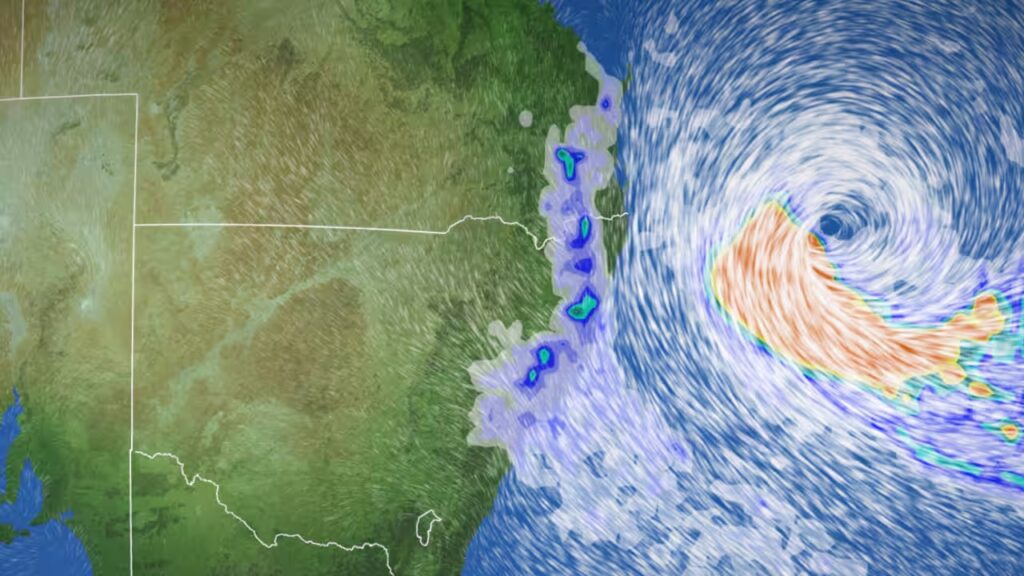

Every El Niño event is different, and this is not the first time we have experienced wet conditions during an El Niño event. However, this El Niño occurred against the backdrop of climate change. A number of factors have converged to create an unusually wet set of conditions since the late spring, including warm waters to Australia’s east and a persistent positive Southern Annular Mode. Many of these symptoms are consistent with what we’ve been warned to expect with worsening climate change.

We are poorly prepared for these changes, and still doing far too little to tackle the root cause of the climate crisis: climate pollution from the relentless burning of coal, oil and gas.

What can we do about this?

The only solution is to end climate pollution as quickly as we can.

Everything we experience today is in an ocean-atmosphere system made hotter

and more energetic by the burning of coal, oil and gas. The more we burn, the more they blanket our planet in heat-trapping climate pollution that supercharges the extreme weather we’re already experiencing.

Australia must urgently cut climate pollution from the burning of coal, oil and gas this decade to protect ourselves, and all future generations, from worsening extremes.

The Climate Council has developed a clear plan for how more Australians can benefit from taking further, necessary steps. Our plan centres around how we build a clean economy to power our lives, set up our communities and kids for success, and end climate pollution.

There’s no time to waste. Everything we do now matters.