After the great deluge saturated huge swathes of our country over the past few years, ‘fire’ might not be at the top of your list of things to worry about. But unfortunately for some of us, it should be. The rain has spurred significant vegetation growth, particularly in our grassland areas, and this is a major threat as we move from wet La Niña conditions to hotter, drier conditions. Traditionally, grass fires follow floods.

Here’s everything you need to know about grass fires – what they are, why they’re so dangerous, and what we can do to stay safe.

What is a grass fire?

In Australia, ‘bushfire’ is the generic term used to describe fires in the landscape. Bushfires can involve different types of forest, shrubland, tropical savanna, grass and crops.

Grass fires are fundamentally different to a bushfire and are generally less intense but equally as dangerous. Grass fires occur in grassland areas where the dominant vegetation is grass, and are unpredictable, start easily and spread quickly – up to three times faster than bushfires. They can move at up to 25km/hr (far too fast for a person to outrun), and pulse even faster over short distances.

Fully cured grasslands can dry out rapidly and ignite within hours of rain ceasing. Dead grass serves as a ‘flash fuel’, and grassy landscapes with high air flow provide plenty of oxygen to feed a fire. Resulting fires can be influenced strongly by changes in wind speed and direction, making them very dangerous and difficult to control on days of serious fire danger.

Introduced weed species are also worsening fire problems across Australia. Native vegetation, which can burn intensely but often self-limits fire spread thanks to its sparse nature, is being overrun by introduced species that burn hotter and faster.

Grass fires can be ignited by, for example, lightning, harvesting accidents, arson, and escaped burnoffs. And once a grassfire starts, it can spread rapidly and ignite nearby vegetation, including trees and shrubs.

What’s happening at the moment

From La Niña to El Niño?

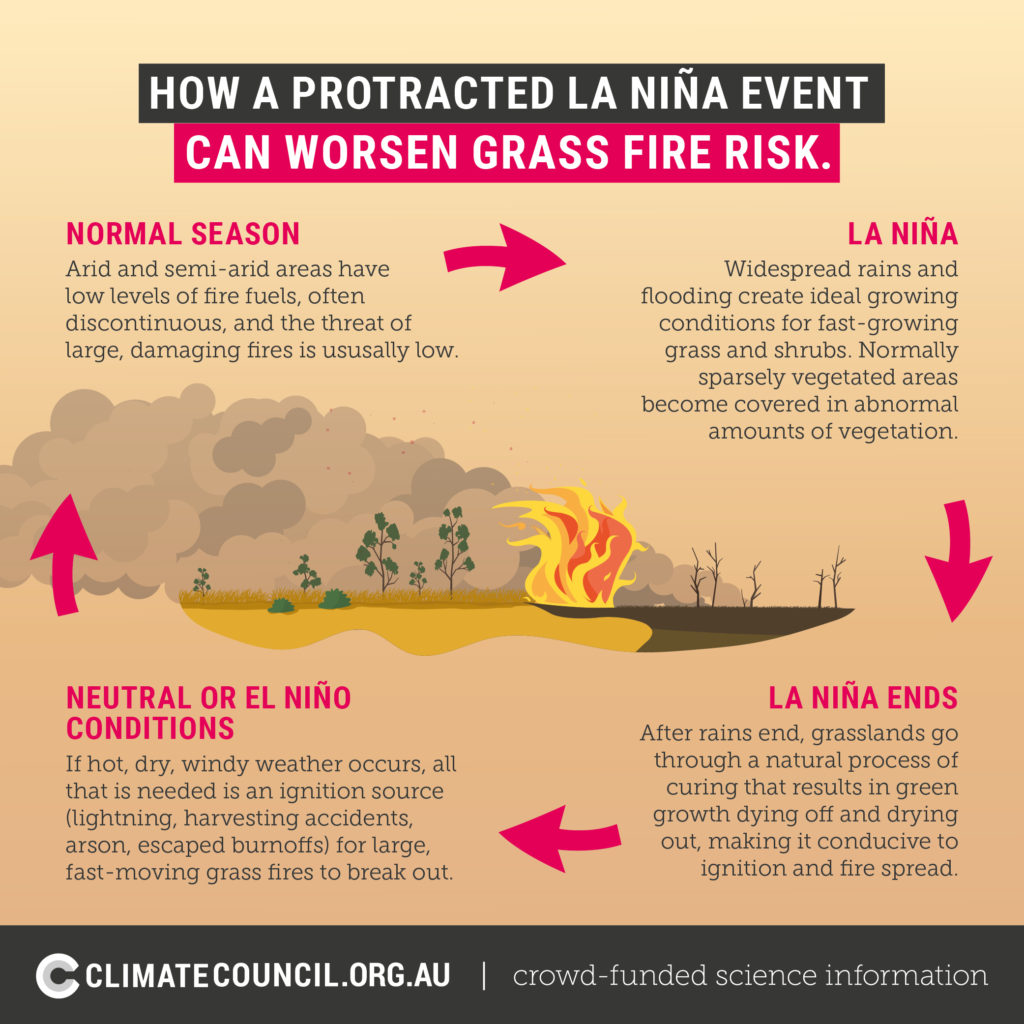

Periods of rain keep vegetation wet, reducing the likelihood of ignition and limiting fire spread during the wet period. However, this can create perfect conditions for prolific growth, even in desert areas that don’t typically have enough vegetation to pose a fire risk.

From 2020 to 2023, Australia experienced a protracted’ (multi-year) La Niña episode that led to record-breaking rainfall and flooding along the east coast. These heavy rains have spurred rapid growth of grass and bushland.

History shows that grass fires follow floods. During protracted La Niña periods since 1950 (1954 – 1957, 1973 – 1976, and 1998 – 2001) high vegetation growth led to extensive grass fires across Australia, followed by major forest fires, which caused loss of life and property damage on the east coast, particularly in NSW. Australia experienced the most widespread grass fires ever recorded in 1974 – 1975, with about 117 million hectares burnt nationally – or about 15 per cent of Australia’s land mass.

Current weather models indicate that Australia could see a return to warmer and drier ‘neutral’ or even El Niño conditions towards the second half of 2023. El Niño is a naturally occurring climate cycle in the Pacific Ocean that brings hotter, drier conditions to eastern Australia, making droughts and bushfires more likely.

What this means

Since the last extended La Niña event, climate change has worsened, intensifying all forms of extreme weather. Firefighters now fear extensive grass fires that break out in hotter, drier, windier weather conditions than those experienced in 1974 – 1975, could be far more destructive and deadly, like those recently experienced in the United States. The spring of 2023 and summer of 2023 – 2024 could herald widespread grass fires, supercharged by climate change.

Fire and emergency services experts in Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Western Australia believe we could experience an increased risk of major grass fires up to, and possibly including, April 2023.

Significant bushfires in Tasmania and NSW in 2013, and the Black Summer bushfires in 2019 – 2020, have shown that El Niño is no longer needed to produce a bad fire season. Even a “neutral” phase (when there is no El Niño nor La Niña climate phenomenons occurring) can now produce periods of extreme or catastrophic fire danger. If an El Niño event does become established during 2023, this will raise the threat of both grass fires and major forest fires.

The collective wisdom of firefighters, based on history and experience, suggests that grass fires are never as damaging as forest fires. However, this may not hold true during a grass fire event that occurs in conditions as extreme as the ones we now experience in a supercharged climate.

Events in Australia, and overseas, prove that grass fires are dangerous when they occur in hot and dry conditions. If the third risk factor, strong winds, also occurs, then Australia could see grass fires unfold on a scale never before experienced.

It’s important to stay informed

If you are in a region with high grassfire risk ensure you are connected to emergency information via the internet, television, radio and/or the emergency service apps, and follow all directions from emergency services.

Find more on what you can do to reduce your risk of grass fires and stay safe here.

What can we do?

Climate change has pushed us into a new era of increasingly severe and frequent disaster threats. Our emergency management, response and recovery arrangements, which were set up to cope with a much tamer environment in the 1990s, are not set up to deal with the scale and frequency of disasters happening today. Without major changes, they will certainly not be able to handle worsening threats as global warming escalates.

Governments at all levels should prepare for a potentially devastating fire season ahead, and help communities cope with worsening and compounding climate impacts, as well as prevent or manage disasters more effectively. Additionally, efforts to adapt and build resilience to climate impacts need to go hand-in-hand with much stronger efforts to move beyond fossil fuels and rapidly cut emissions which can avert even worse catastrophes.