Two of Australia’s expert government agencies, the Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO, have released the ‘State of the Climate 2024’ report, and it’s a big deal.

The report, released every two years, confirms what millions of us are experiencing: we are living in the era of climate consequences.

Let’s break it down.

What is the ‘State of the Climate’ report, and who wrote it?

‘State of the Climate’ draws on the latest national and international climate research, encompassing observations, analyses and future projections, to describe longer-term changes in Australia’s climate. The report is prepared by the Bureau of Meteorology and CSIRO and is intended to inform economic, environmental and social decision-making by governments, industries and communities.

We’ve read the report so you don’t have to. Here’s what it says:

Supercharged by climate pollution from the burning of coal, oil and gas, Australia’s weather is becoming more volatile. In this warmer, wetter world, we are experiencing worsening extreme weather events, like heatwaves (land and sea), longer fire seasons, more intense heavy rainfall, and sea level rise.

Ultimately, our climate science and meteorological experts have produced a report that makes for scary reading for all Australians. Let’s take a look now at some of these frightening findings.

Scary finding #1: Warming oceans and rising seas

Oceans around Australia are continuing to warm, with increases in global climate pollution creating more acidic oceans, particularly south of Australia.

Increases in temperature severely damage marine habitats, species and ecosystem health, with the most recent mass coral bleaching event on the Great Barrier Reef this year confirming this stark reality. Rising sea levels around Australia are also increasing the risk of inundation, threatening coastal communities and critical infrastructure.

Figure 1: The occurrence of extreme heat in Australia is increasing. Source: BoM and CSIRO 2024.

Scary finding #2: Global warming and drought trends

Australia’s climate has warmed by an average of 1.51°C since national records began in 1910, with eight of the nine warmest years on record having occurred since 2013.

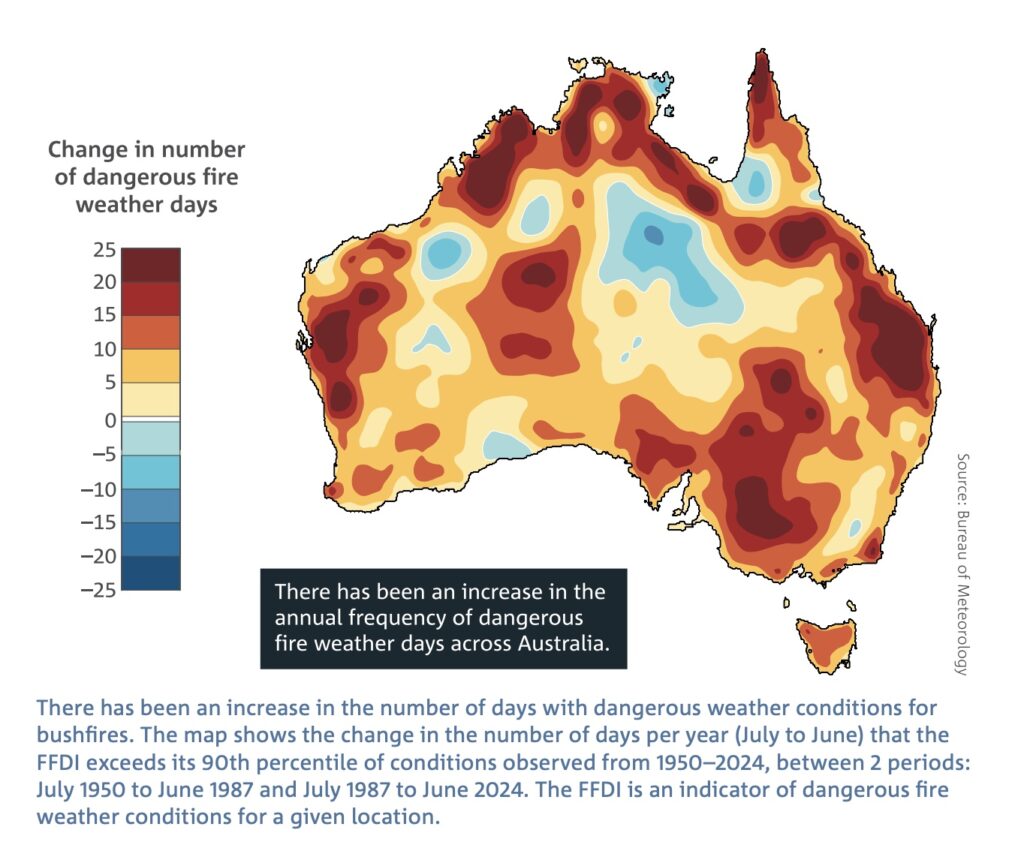

This warming has led to an increase in extreme fire weather and longer fire seasons across large parts of the country. There has also been a shift toward drier conditions between April to October across the southwest and southeast, while reduced rainfall in southwest Australia now seems to be a permanent climate feature. Meanwhile, lower rainfall in the cooler months leads to lower average streamflow in those regions, impacting soil moisture and water storage levels and increasing drought risk.

The report also found that droughts this century have been significantly hotter than those in the past, and that when heavy short-term (e.g. hourly) rainfall events do occur, they are becoming more intense, with an increase of around 10 per cent or more in some regions. The largest increases in heavy rainfall are in the country’s north, with 7 of the 10 wettest wet seasons since 1998 occurring in northern Australia.

The bottom line

The effects of climate change are hitting us hard, and playing out in real time across every corner of the country. Climate pollution, caused by the burning of coal, oil and gas, is fuelling increasingly severe bushfires, floods, heatwaves and destructive storms. As a result, the overwhelming majority (84%) of Australians report having been directly affected by at least one climate-fuelled disaster since 2019.

Australians have also felt the rapidly increasing cost of these unnatural disasters over the last decade. Before 2000, extreme weather events and disasters cost Australia about $2.5 billion per year in insurance claims for loss and damage to assets (adjusted to 2022 dollars and property values). But since 2010, the cost of damage caused by unnatural disasters has grown by over 60 percent, to $3.7 billion a year, and the last five-year average has increased to an eye watering $4.5 billion in payments by insurers to policyholders impacted by extreme weather events. As of August 2024, the Actuaries Institute estimated the rising cost of home insurance premiums have caused the number of Australian households experiencing home insurance affordability stress to rise by 30 percent, to 1.6 million in the past year.

Figure 5: Unnatural disasters in Australia are becoming significantly more expensive to recover from and insure against.

Source: Climate Council analysis, based on ICA (2024), Finder (2024) and ABS (2024).

In spite of the considerable progress we are making in clean energy and transport, with roughly 40% of our main energy grid now powered by clean energy and Australians embracing electric vehicles like never before, the state of our climate is bad and getting worse.

We are approaching the middle of the critical decade for cuts to climate pollution, and everything our governments do matters. Now is the time for all levels of government to accelerate their efforts to slash climate pollution further and faster, and protect more Australians from avoidable escalations in heatwaves, bushfires, cyclone intensity and floods.