A fundamental duty of governments is to keep people safe. Wherever we may live, having a basic level of physical security and the confidence that we are safe and protected at home is essential. For too many of us worsening fires, floods, storms and droughts — driven by climate pollution from the burning of coal, oil and gas — are eroding our security.

An overwhelming majority of Australians have experienced at least one climate-fuelled disaster since 2019 and around one in three of us worry we may one day be forced to relocate.

We are now living through a rapid intensification of climate-fuelled disasters. Emergency services and governments worldwide are already being periodically overwhelmed by the increasing frequency, intensity and destructiveness of climate-fuelled disasters, and this will continue to worsen until we stabilise temperatures. If we are to have any hope of successfully coping, all adaptation and resilience efforts must sit alongside urgent efforts to reduce climate pollution further and faster this decade.

The following five priorities identified by Emergency Leaders for Climate Action (ELCA) are concrete steps Australian governments can take to help better protect communities from the impacts many are already experiencing due to climate pollution.

Key Findings

1. Communities and first responders are struggling to cope with increasingly frequent climate-fuelled disasters, with assistance from the Australian Government sought by states and territories 226 times since 2019/20.

- Financial assistance has been called for and provided by the Australian Government in response to disasters 226 times over the past five years, with four out of five of local government areas across the country impacted.

- Some communities are being repeatedly pummelled by fires, floods and storms with little time to recover

in between. The highest incidence of disasters were recorded in Baw Baw (47), Yarra Ranges (42) Wellington (37) and East Gippsland (39) in Victoria; Clarence Valley (34), Mid Coast (33) and Port Macquarie (30) in New South Wales; and Cook (28) and Carpentaria (25) in Queensland. - Emergency services, local governments and communities have struggled to cope with the frequency, intensity and destruction of disasters like the Black Summer bushfires and flood emergencies during the back-to-back La Nina years of 2020-2022. Smaller communities already have too few emergency service volunteers to adequately respond to such disasters. Under-funded and under-resourced local governments struggle to cope with ongoing recovery from disasters long after emergency services and the media have left.

- Emergency Leaders for Climate Action recommends building community resilience through locally-based teams of volunteers, working with support and coordination provided by local emergency services and councils. These volunteers can then lead on-the-ground preparation and recovery from disasters.

- A new program of paid seasonal firefighters should be piloted during periods of heightened bushfire risk to bolster the ranks of urban fire services on the urban / bushland fringe and to provide back up and relief for volunteer rural fire services.

2. Australians have been forced to move almost a quarter of a million times

in recent years due to climate-fuelled disasters, with certain communities becoming calamity hotspots.

- National data shows that between 2008/09 and 2022/23 there were 240,828 displacements – or forced movements – across Australia due to extreme weather events. Two thirds of these occurred between 2018/19 – 2022/23.

- Of the 95,239 displacements resulting from fires, 68% were due to the unprecedented Black Summer bushfires. Two thirds (68%) of the 85,690 displacements from floods were due to 2020-22 flooding disasters in Queensland, New South Wales and Victoria. Tropical cyclones Debbie (2017), Yasi (2011) and Oswald (2013) accounted for 79% of 59,826 displacement due to storms.

- People are also experiencing long periods of homelessness following a climate-fuelled disaster. For example, following the October 2022 floods that engulfed Rochester, Victoria it was estimated 70% of residents still weren’t able to return home seven months later.

- Wherever possible, people should be supported to remain where they live. When the safest choice is to move people out of harm’s way (for example, relocating from flood plains), they should be supported to move safely, with dignity and fair compensation.

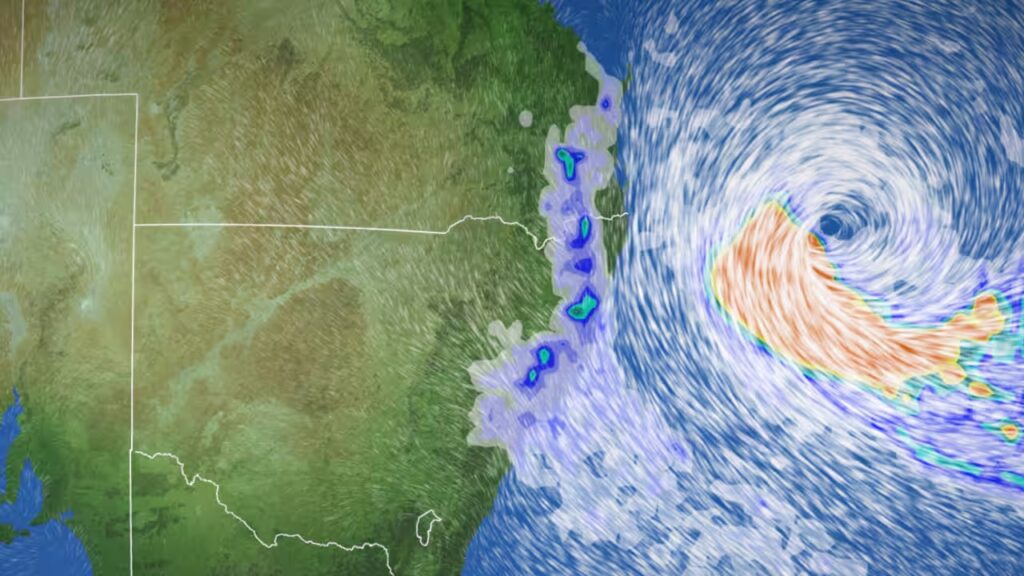

3. We can limit the severity of future floods, fires and destructive storms if we phase out pollution from coal, oil and gas more swiftly in the 2020s.

- 2023 was the hottest year on record globally, with 2024 shaping up to match or exceed this: driven by climate pollution from the burning of coal, oil and gas.

- Scientists are clear that climate pollution is causing more chaotic and extreme weather events including longer, hotter and more frequent heat waves, longer and more ferocious fire seasons, and flooding rains.

- Emergency Leaders for Climate Action believe that all governments must accept climate change as an existential threat and mobilise urgently to tackle the root cause of worsening extreme weather: pollution from coal, oil and gas. Climate Council research spells out how Australia can cut climate pollution (Climate Council 2024c) further and faster across our economy in the 2020s.

- There is still considerable scope to limit the severity of future floods, fires, heatwaves and destructive storms if we seize the decade, build up clean energy infrastructure and industries and cut climate pollution deeply by 2030.

- While we rapidly decarbonise the economy, we must simultaneously invest urgently in climate adaptation and disaster resilience to protect communities from the effects of climate pollution already in the atmosphere.

4. Australia is making inroads to better prepare for and respond to worsening extreme weather, but efforts remain underfunded and inadequate in the face of the climate challenge we now face.

- The Australian Government should be commended for setting out to rebuild Australia’s capacity to deal with climate-fuelled disasters after a decade of neglect, but much more remains to be done.

- The Australian Climate Service should be adequately resourced to become a “single point of truth” providing communities, businesses and governments with accessible, consistent climate risk information and predictions downscaled to regional level, as a basis for informed decisions.

- We don’t yet understand which communities are most vulnerable to climate-fuelled disasters — or less able to prepare or respond — due to existing inequalities and social demographics. This information is crucial to preparing communities for disasters and supporting them to respond and recover.

- Governments must go beyond rebuilding and repairing physical infrastructure after a disaster, with research showing that community connection and social capital strongly influence how people are able to prepare for and respond to a disaster.

- Communities can be empowered and resourced to comprehend their own level of risk using reliable data, and then develop their own resilience measures, assisted by emergency services, all levels of government, and the private sector.

5. We can keep our communities safer from the climate impacts of today and tomorrow with better information, access to support and by heeding the lessons of past disasters.

- Targeted support is required to make sure we prioritise the people and places most at risk from climate-fuelled disasters, and those least able to prepare and respond.

- Investing in social connection and capacity within communities, as well as resilience for individual households, will make them better equipped to prepare and respond. Dedicated funding is needed for community-led initiatives at local government level.

- Australian, state, territory and local governments should respond in full to each and every recommendation arising from the Royal Commission into National Natural Disaster Arrangements, as well as recommendations from state/territory flood and fire inquiries conducted since 2019.

- The Australian Government has committed additional funding to the Royal Commission recommendation to create a sovereign aerial firefighting capability to reduce reliance on large firefighting aircraft rented from overseas. Opportunities exist to trial different types of firefighting aircraft, to retain and repurpose retiring RAAF C130-J aircraft, and use local pilots and servicing capabilities, to establish a year-round local capability that could also move people and equipment during extreme weather events.