A reflection on black Saturday by former fire and emergency leaders; Craig Lapsley, former Victorian Emergency Management Commissioner, Russell Rees, former Chief Fire Officer of Country Fire Authority Victoria, and Ewan Waller, former Chief Fire Officer of Forest Fire Management Victoria.

Find out more about the Emergency Leaders for Climate Action here.

Fifteen years on from Victoria’s worst bushfire disaster, the wounds still run deep. They run deep for friends and loved ones of the 173 people who died that day, for the more than 2,200 families made homeless and for the traumatised communities and firefighters who faced what, until then, was an unprecedented disaster. Together with our agencies, we learnt painful lessons about how fires need to be managed in this changed environment.

Back in 2009, we knew that climate change, caused by the burning of coal, oil and gas, was driving more intense extreme weather events. We had been warned of this since the mid-1990s. But during Australia’s political climate wars, as community leaders our concerns about this were given only cursory acknowledgement.

The Canberra firestorm of January 2003 was a foretaste. We saw the first large-scale fire tornado and the fastest rate of spread of a bushfire ever recorded worldwide.

A sense of dread started to take shape for those of us serving in Victoria, which is acknowledged as one of the most fire prone places on earth. What if we were to get similarly off-the-scale weather conditions her

Sadly, on 7 February 2009, we found out.

In the hot, dry lead-up to Black Saturday, fires were bigger and harder to fight. On Feb 7 we faced the worst fire conditions we could’ve imagined. Our crews were up against blistering temperatures, as well as storm-force winds that caused them to seek shelter wherever they could and stopped water-bombers from flying. Our traditional fire fighting systems and our communications simply could not keep up.

Once rare (but now common) fire-generated storms blasted communities like Kinglake with more energy than dozens of Hiroshima-sized atomic bombs. The fire danger index, with a theoretical maximum of 100, recorded figures greater than 200.

Things clearly needed to change. The resulting Royal Commission and other investigations created fundamental changes to national fire service doctrine. Leaders around the country embraced evacuations and emergency warnings, so that people would know when to get out and stay out, or when it was too late to leave.

More active landscape management including enhanced prevention through a broad area forest fuel management program was recommended. We all hoped these lessons had been learnt and things would be better with improved systems but as extreme weather events continue to become more frequent and more intense, we are playing a deadly game of catch-up.

Fast forward 10 years to Black Summer and some of those fundamental policy shifts probably saved hundreds of lives. Yet many died and more than 3,000 families were made homeless.

Nobody can say we weren’t warned. Decades ago, scientists explained how the relentless burning of fossil fuels was warming the planet. They told us it was making our weather more extreme, that it was worsening fire conditions, and that it was driving wild swings from hot and dry to storms and floods and back again.

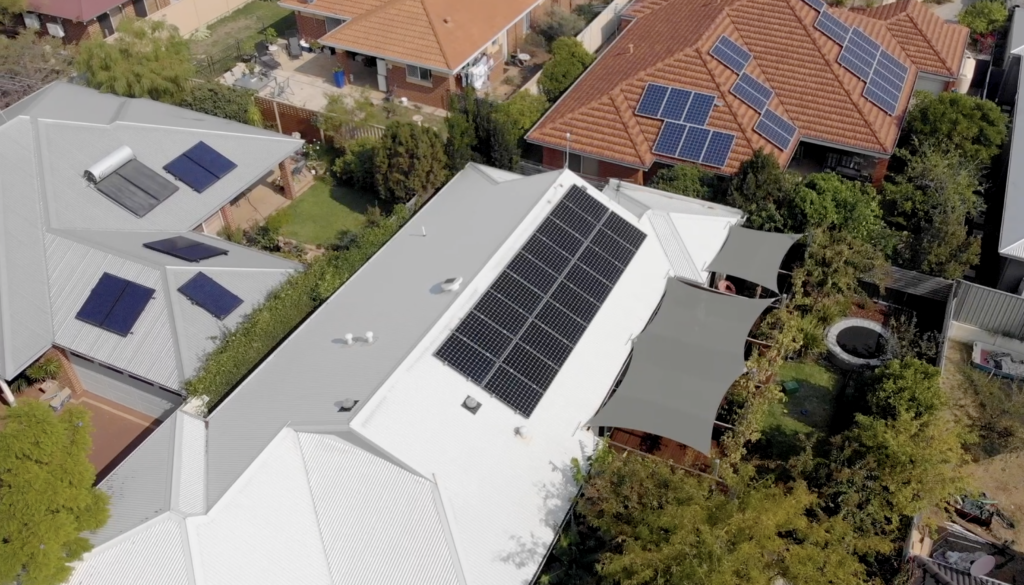

But because of political ideology, the financial might of the fossil fuel industry, and determined campaigns of misinformation, the experts were sidelined. Governments sat on their hands for nearly a decade. The necessary moves to slash climate pollution by shifting towards cleaner and safer energy sources like solar and wind are finally taking hold, but still at an insufficient pace to protect families, communities and nature.

If Australia and the world at large leave polluting fossil fuels in the ground, we will substantially limit the severity of these disasters over the longer term. Australia, with its abundant solar and wind resources, has a major role to play. We have a shot at limiting fires like those of Black Saturday, sparing communities’ grief and giving the next generation hope – but we are running out of time.

Today, many tears will flow across the nation. Together with many others who tried in vain to battle the brutal blazes that overtook our state, we will recall things that we wish we could forget, and those painful lessons learnt on that day.

We will also remember the loved ones lost, the firefighters who faced scorched landscapes, and the millions of animals killed.

We will be thinking about the future we want for our children and grandchildren – and hoping we don’t squander another second on climate inaction.